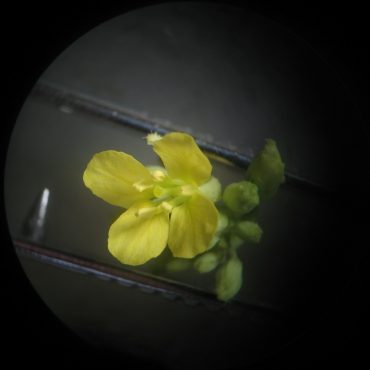

Ecology

Black mustard flourishes in disturbed areas59 and rarely invades established native vegetation.174,353 Re-occupation of a black mustard stand by native plants is slow. Several factors have been implicated in maintaining this strong spatial dominance of black mustard.

Like the related wild radish, black mustard lacks the symbiotic, or mutualistic, relationship with soil fungi – a “mycorrhizal association”161 – that characterizes many of our native plants and facilitates their uptake of water and nutrients from the soil.41,153,155 In the absence of the soil fungi, mycorrhizal plant growth is impeded.59,155 Because black mustard lacks this mycorrhizal dependence, the absence the mutualistic partners does not restrict its growth, giving it a competitive advantage over native plants in areas where the soil has been disturbed.

In addition, black mustard produces allelopathic compounds that may inhibit the germination of surrounding plants.183,355Compounds leaching from dead stalks and leaves have been shown to reduce germination of non-native annual grasses in California grasslands and may also inhibit native plants.

Black mustard may also reduce the re-establishment of new native plants by shifting herbivory away from the mustard patch to other plants.356 The seeds of black mustard are too small for most seed-eating mammals. A stand of black mustard offers physical refuge to a variety of small mice and rabbits but mammals must forage elsewhere. The amount of seedling production of a native bunch grass, Stipa pulchra, is strongly dependent on the distance from a mustard patch, approaching zero at the edge of the patch and effectively eliminating the possibility that the bunch grass will recolonize the mustard habitat.

In spite of persistent eradication effort in the Reserve, black mustard returns each year – an ornery guest that refuses to take the hint.