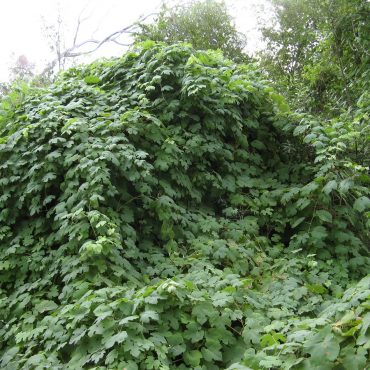

Plants in riparian forests must either be shade-adapted or compete with their neighbors for sunlight. Most trees produce woody support structures – trunks and branches – that lift their leaves above the surrounding vegetation into the sunlight. However, these woody structures require energy to produce and maintain, energy that must be diverted from photosynthesis and reproduction. A significant number of species have developed a vining strategy, forgoing their own support tissue and using surrounding plants as support. This allows them to grow very fast and gives them slim, flexible stems that will bend, twist and stretch rather than break. Vines have several types of climbing gear: the stems may twine around the support like wisteria (Wisteria spp.), tendrils may grab and hang onto smaller branches and twigs, like wild cucumber (Marah macrocarpa) and ropevine clematis (Clematis pauciflora), downward pointing hairs may cling like Velcro, like fiesta flower (Pholistoma auritum); in some cases special structures have adhesive pads that glue them in place, like Boston ivy (Parthenocissus tricuspidata).

Desert grape is the largest vine in the Reserve and it clings by means of forked tendrils from the stem, pulling itself up surrounding shrubs and trees. This allows it to raise its leaves high above the willows, mulefat and sapling sycamores that surround it.

A dominance of vines in an area, has ecological consequences for the surrounding system. Vines overgrow and suppress, even kill, smaller or slower growing plants. On the other hand, they benefit the wildlife by providing arboreal habitats and corridors not present before, and by replacing original food sources with a new one. Desert grapes are especially useful for wildlife. Whether the net change is good or bad, depends upon the goals and aesthetics of the observer.