Mission manzanita is a much branched, upright shrub with one or several trunks from an underground burl. Although it is generally reported to be less than 10 feet (3 m) in height at least one 20-foot (6m) specimen has been reported from Peñasquitos Canyon,315 where it grows from a burl over 5 feet (1.5 m) in diameter and is estimated to be over 100 years old. The smaller branches have rough gray bark that sheds as they age, leaving smooth, reddish trunks, similar to trunks of true manzanitas The leathery leaves are elliptic to oblong, 1 to 2.5 inches (2.5 – 6.5 cm) long, from short petioles. Margins are smooth and are rolled under. Leaves are smooth and green on top; the underside is loosely covered with soft hairs, which give the lower surface a pale hue. Leaves may be opposite or alternate.

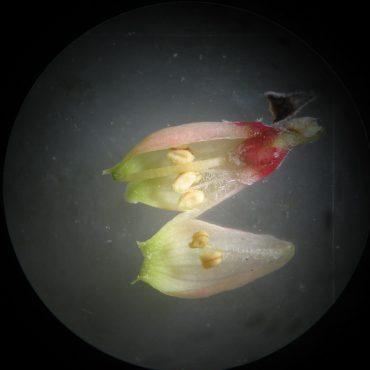

The flowers also resemble those of true manzanita. They are urn- or bell-shaped, approximately 3/8 inch (0.9 cm) long and hang upside-down in clusters at the ends of the smaller branches. Clusters usually have less than 2 dozen flowers that tend to open at different times. There are five (or four) dark pink sepals, united at their bases, with broad, overlapping lobes. Five (or four) white to pink petals are united into a bell shape with a narrow mouth with overlapping, greenish lobes, which flare outward. There are generally ten stamens (our plants often have five), completely retained within the corolla. The lower half of the filaments have long hairs. Anthers release their pollen through small, terminal slits. The single ovary is superior, with one cylindrical style and a green, minutely lobed stigma, which barely extends beyond the corolla. The style turns reddish brown and persists on the developing fruit after the petals have fallen. Flowers occur December – March.1

The shiny red to black fruit are about 1/4 ” (5-8 mm) wide and resemble berries. Technically they are “drupes” with a thin exterior fleshy layer enclosing a very hard-walled seed chamber that contains up to five seeds. Fruit may persist on a plant through the summer.