Ecology

Any one who has visited TPSR early on a foggy day knows that each tree becomes a little rain cloud, sending water dripping to the ground (and the person) below. Plant ecologists generally agree that fog can be a significant source of water in some areas, especially during periods of little or no rainfall. This “fog drip” has been shown to be important in several environments 41,368, 369,370,371 including montane cloud forests and the coastal evergreen forests of northern California. In these habitats, fog drip may equal or exceed rainfall amounts.

In coastal southern California where annual rainfall is very limited, cloud shading and fog drip significantly reduce drought-stress in pines.368,369,372,373 Because fog here occurs primarily in the summer when rainfall is often absent, the effect of even a little fog drip on tree growth appears to be very important – possibly making the difference between survival and death in a very marginal habitat.

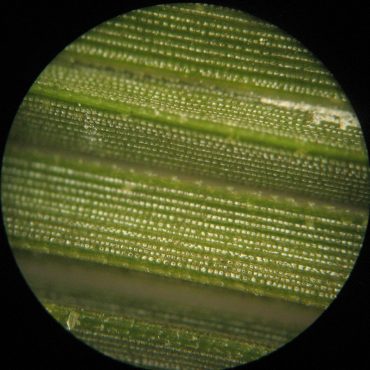

The needles of conifers appear to be especially well suited for fog capture,374 perhaps because larger leaves divert airflow around and past their surfaces while the flat or thin needles promote direct collision and capture.375 In a two-year science project a local school student, Brock Oury, while in 7th and 8th grades, designed a fog chamber with which to compare the fog drip of Torrey Pines with that of four other pines. The Torrey needles condensed the most water. Brock speculated that this was due to the larger size and number of needles in a bundle.376 In the second year, this project was extended and the needles of the five pines were examined microscopically.377 Needle surfaces are sculpted with many series of microscopic projections that define tiny channels running the length of the needle. The projections on the Torrey pine needle are both larger and more numerous than those of the other species and Brock speculated that these are the sites of fog condensation, where the tiny fog droplets are captured and merged into larger drops that move down the channels and off the needle to the ground (or person) below. Brock’s second-year project won first place at the State Science Fair in the category of Plant Biology.378,379 Nice job, Brock.

Note: Earlier this year, 2017, another local student, Emily Tianshi won national recognition for her studies on the fog-capturing abilities of the Torrey pine 380 but so far we do not know the details of the project.