The wild radish (Raphanus sativus) is not native. The neat, tidy little radish plant of farms and gardens has given rise to a tall, gangly, unruly upstart – a troublesome pest that fluorishes in disturbed areas throughout the state. In the Reserve, it often forms large, colorful patches along the trails and in areas formerly tilled by early farmers. It is one of a few species examined as of 2015 that does not need to partner with a soil fungus for rapid growth. This allows the wild radish to out-compete our native plants in areas where the soil has been disturbed and the soil fungi eliminated.

Wild Radish (not native)

Raphanus sativus

Other Common Names:

California wild radish, radish, jointed charlock

Description 2,4,11,34

Wild radish is a non-native annual or biennial plant that is common in disturbed areas and is considered a pest in the Reserve where it can quickly cover large areas, preventing the re-establishment of native species. The plant is generally less than four feet (1.2 m) tall. There is basal rosette of large pinnately divided leaves, each with a large terminal lobe. Basal leaves have petioles. There is a gradual transition from the basal leaves to the upper cauline leaves which are smaller, sessile and unlobed with toothed margins. Leaves are often prickly with small stiff hairs.

Flowers open sequentially, forming many-flowered, open spikes at stem ends. En masse, radish flowers provide a spectacular display. Flowers are bisexual, radially symmetrical one-half to one inch (1.2 – 2.5 cm) in diameter. There are four green sepals in two pairs that form a narrow tube, somewhat constricted in the middle. There are four petals, each of which has a long, narrow basal portion, which is hidden by the sepals; at the top of the sepals, each petal flares outward, the four petals forming a cross. Petals can be white, yellow, pink, purple, or bronze, often shading to white at the throat; veins may provide delicate stripes of a darker hue. There are six stamens in two series: a ring of four longer stamens protruding from the flower throat, and two shorter stamens outside the ring. A slender pistil with a small rounded stigma protrudes from the flower’s center. Bloom period is February – July.1,7 In the Reserve, peak bloom is March – April, but some flowers may be found all year.

The fruits are slim cylinders, one and a half to three inches long (3.8 – 8 cm), beaked at the top and bulging somewhat at the seeds. Initially, the ovary is enclosed by the sepals and petal claws; these drop soon after pollination. Fruits develop progressively below the flowers. Mature pods are brown and woody with two to eight seeds embedded in a spongy matrix. There is disagreement on whether or not the seedpods split open at maturity. One source11 writes “The swollen cylindrical seedpods break transversely with each portion carrying one to several seeds…” Another source4 writes that the pods do not split open at maturity; instead, seeds germinate from within seed chamber. Yet another source writes “When the fruits dehisce [split open] they often leave a single seed still adhered to the plant”.154 Anyone who would like to sit and document one of our radish seedpods maturing, please contact us.

Distribution 7,89

Radish is thought to be native to SE Asia,41 possibly China155 but has been farmed and become naturalized worldwide, including most states in the US.89 It is most common in disturbed areas in many vegetation types below 2000 feet.89

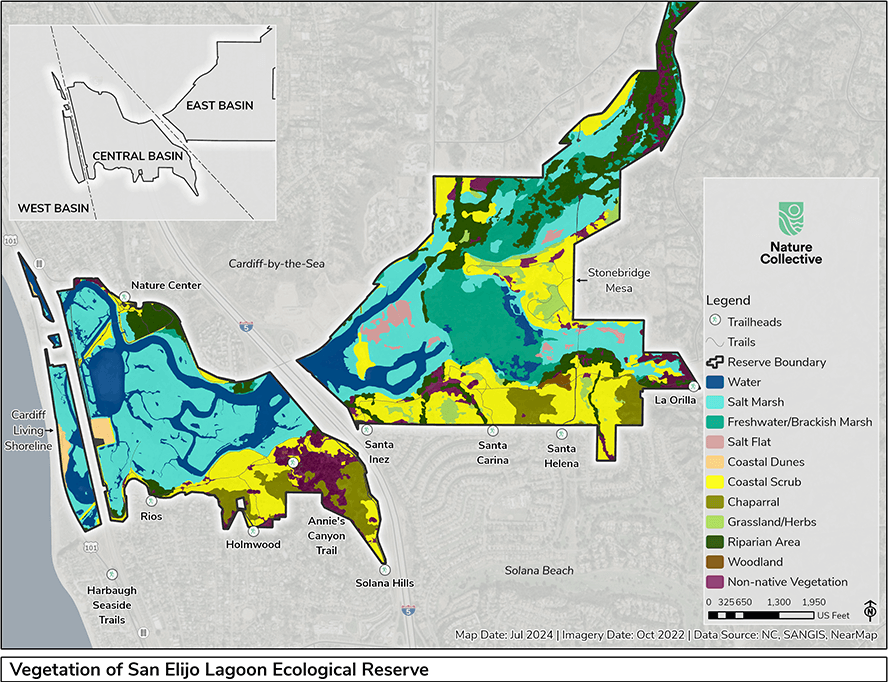

In spite of intensive efforts to remove it from the Reserve, wild radish persists abundantly in open areas along the trails. At the time of writing (March 2015) displays of blooming wild radish are easily seen along the Rios trail, just east of the trailhead, and scattered populations occur commonly elsewhere on both sides of the lagoon.

Learn more about plant vegetation types here

Classification 2,59,143

Wild radish is a dicot angiosperm in the Brassicaceae or mustard family, a family of major economic importance that has very broad distribution. There are many well-known species and cultivars in the family including vegetables such as cabbage, cauliflower, broccoli, turnips, water cress and radishes, and ornamentals such as sweet alyssum and stock. Interestingly, six of our common vegetables–cabbage, cauliflower, kohlrabi, Brussels sprouts, broccoli, and kale–were all bred from a single species of mustard, Brassica oleracea. The mustard family also includes some rampant weeds.

Members of the mustard family are characterized by four petals in a cross shape (from which came the former family name Cruciferae, or cross-bearing); and by six stamens, four long and two short. Mustard seed pods come in a variety of shapes. When mature, they split open from both sides, exposing the seeds attached to a central membrane. Twenty-two species in the mustard family have been reported from the Reserve.48 Fourteen of these are non-native weeds, but included in the others are lovely spring flowers such as wallflower (Erysimum capitatum) and milkmaids (Cardamine californica).

Two species in the radish genus, R. sativus (the garden radish) and R. raphanistrum (jointed charlock, generally considered a weed) have naturalized in California. Both were introduced in the 1800s; radish was brought in as a food crop while jointed charlock was introduced accidentally.152 There is growing evidence that the existing wild population is a hybrid between the two and that the original species no longer exist in the wild.150,154 Both fruit morphology and root morphology of wild plants are intermediate between the two parent species. The great variability of flower color arises from the interplay of two pigment systems, anthocyanin (pink and purple colors) from cultivated radish and carotenoids (yellow) from jointed charlock; white flowers lack either pigment.151 At present, most scientists retain Raphanus sativus as the scientific name for these hybrid populations, but many have adopted “California wild radish” as the common name.152,154 The rapidity of this transformation has made the wild radish a “lab rat” for studies of hybridization, evolution, and extinction.150,152

Alternate Scientific Names:

Raphanus raphanistrum var sativus

Ecology

Many plant species have evolved a complex, symbiotic (mutualistic) relationship with soil fungi.32,162 The association is called a mycorrhiza (although the term is sometimes applied to the fungal partner). The fungus provides a conduit between the soil and the plant’s roots that facilitates the movement of mineral nutrients and water to the plant; it may also provide protection from pathogens and toxins. In exchange, the fungus receives a steady supply of carbohydrates such as glucose and sucrose from the partner plant.41,153,155 In a mature soil, there is a network of mycorrhizal fungi that is an important component of the soil structure. Grading, tilling or fire destroys this network, and in such soils, plants accustomed to the mycorrhizal partnership do poorly until the soil fungi have reestablished.59,155

Most species in the mustard family, including wild radish, are not mycorrhizal.161 They often thrive in the absence of root fungi such as in burned or farmed areas. Thus plants in the mustard family may have a competitive advantage over native plants, quickly forming dense populations in disturbed areas and slowing or preventing the reestablishment of native flora.59

Human Uses 148,149

Radishes have been cultivated for at least 8000 years. They were a staple food for the laborers who built the Egyptian pyramids. As a token of good will, early China gave the radish to Japan where it soon became a favored vegetable. Ancient Greeks offered gold radish replicas to their god Apollo, the multi-faceted god of light and sun, truth, prophecy, healing and plague, music and poetry. In the 14th Century, the radish was introduced to England where it was thought to have medicinal value, curing everything from kidney stones to bad complexions. As a component of the modern vegetable garden, radish is virtually universal. The 2015 on-line Burpee catalog lists seeds for 28 different types of radish.

Native Americans have had only recent experience with radish, too recent perhaps to fall into the purview of most ethnobotanists. In the early 1900s, the Kumeyaay people boiled the leaves as a vegetable and made the seeds into an eye wash.16

The tender young seed pods are edible,34 with a flavor like a radish. They make a tasty snack for hungry docents.

Interesting Facts

In the Reserve, a constant battle is waged against wild radish.160 In the past, areas have been totally cleared of these plants only to have them return with vigor the following years. Community volunteers have spent many man-and-woman-hours removing wild radish from our restoration sites.